100 Haiku for 100 Years:

|

ISBN: 1-929820-14-6 Brooks Books out ot print |

|

unable |

in Sobi-Shi's glass |

|

boiling beet tops |

under |

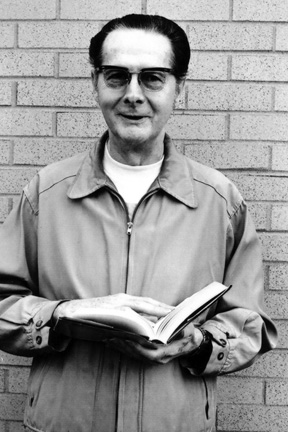

Widely published and recognized as a master of traditional English verse forms, in 1960 Roseliep began writing haiku, at first in the traditional 5-7-5 form, then in more experimental ways. His first book The Linen Bands was published by The Newman Press in 1961. Roseliep published over twenty books, including Rabbit in the Moon, Step on the Rain, The Still Point, Light Footsteps, and Firefly in the Eyecup. In 1964 he was the Poet-in-residence at Georgetown University. In addition to the major haiku journals which published his work regularly, more than ninety other magazines have printed his haiku, and he appears in many anthologies and in a growing number of textbooks. His haiku attracted critical praise from such poets as W.H. Auden, Josephine Jacobsen, Denise Levertov, William Stafford, X.J. Kennedy, and A.R. Ammons. In 1982 he was appointed Professor Emeritus at Loras College. Father Raymond Roseliep died on 6 December 1983 of an aneurysm. For Raymond Roseliep the two most sacred themes were creation and love, so it was only natural that he would explore both in his haiku. In an interview first published in 1979, Roseliep was asked how a priest could be writing such evocative, sometimes erotic, love poetry. “To talk about that,” Roseliep said, “I should return for a moment to that Catholic-poetry period of mine, and I can briefly tell you how it was inevitable that I needed a fresh theme. In those early days I was writing about the Mass, the sacraments, parish experiences, religious encounters of all dimensions — in people, nature, anywhere.” He added: “I needed a new outlook. I knew that religious poetry and love poetry are the hardest of all to write, and since I hadn’t attained full success in one, I would try the other. And I have been exploring the love theme ever since. It’s wonderful. It keeps me alive and young and remembering; and always with feelings that are deepest and most sacred in all of us.” (Delta Epsilon Sigma Bulletin24:4 (December 1979); A Roseliep Retrospective: Poems & Other Words By & About Raymond Roseliep (Ithaca, N.Y.: Alembic Press, 1980), 13.) Biography from The Living Haiku Anthology. |

|

This Haiku of OursAn excerpt from Raymond Roseliep’s “This Haiku of Ours,” published as a letter to the editors in Bonsai: A Quarterly of Haiku in 1976, pages 11-20. Dear Jan and Mary, Since 1963 I've been working with haiku—reading Japanese haiku of all ages in translation as well as varieties of haiku by American and English writers, studying articles and books about this exquisite formation, and of course writing haiku, ranging from classical /traditional on through vastly experimental kinds. Although my theory and practice are both in a healthy state of flux, I'd like to set down some of my present thought. Marveling at how we've done splendid, audacious things with the sonnet in transporting it from Italian shores into the mainstream of our poetry, I'm heartened to reflect on possibilities for haiku. I believe we are preserving the quintessence of haiku if we do what the earliest practitioners did: use it to express our own culture, our own spirit, our own enlightened experience, putting to service the riches of our land and language, summoning the dexterity of Western writing tools. The most obvious way we can begin to make haiku more our property is to exploit our fabulous native tongue. English can be as musical as only a poet knowing the keyboard can make it, or as cacophonous as he may wish to make it too. Within our miraculous sound system we have cadences, rhythms, measures, movements, stops, pauses, rimes (!). We possess a gigantic vocabulary—and oh what we can do with words when we arrange them! Since phrasing is vital to haiku, our supple American idiom stands ready for achieving any effect desired, and waits only the hand of the poet to manage it. For subject matter we should dig into our own teeming country, God's plenty when it comes to materials: outer space discoveries, hairy youth, mini-skirts, bell bottoms, roller skates, pizza, peanut butter, saucer sleds, circuses, our enormous bird-fish-animal-&-insect kingdoms, our homeland flowers-trees-plants-grains-vegetables-&-fruits, motorcycles, ships that plow the sky and deliver people to Japan—the storehouse is without walls. Practically everything under the sun is valid subject matter for haiku as for any poem, except that in haiku it is the affinity between the world of physical nature and the world of human nature that concerns us. and so we focus our images there. It's American images I'm advocating rather than the Japanese cherry blossoms, kimonos, rice, tea, temple bells, Buddhas, fans, and parasols that populate so many supposedly Western haiku; something is not quite right when our poems come out sounding like Eastern poems. Creation is still more exciting than imitation. ~ Raymond Roseliep |

|

Raymond Roseliep was a poet and contemporary master of the English haiku and a Catholic priest. He was born on 11 August 1917, in Farley, Iowa. In 1939 he graduated from Loras College with a Bachelor of Arts, in 1948 he received a Master of Arts in English from Catholic University of America, and in 1954 he received a Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature from Notre Dame University. He was ordained on 12 June 1943 at St. Raphael’s Cathedral, Dubuque, Iowa. During the mid-50’s Raymond Roseliep began writing poetry that is less that of a “Catholic priest” and more secular in nature.

Raymond Roseliep was a poet and contemporary master of the English haiku and a Catholic priest. He was born on 11 August 1917, in Farley, Iowa. In 1939 he graduated from Loras College with a Bachelor of Arts, in 1948 he received a Master of Arts in English from Catholic University of America, and in 1954 he received a Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature from Notre Dame University. He was ordained on 12 June 1943 at St. Raphael’s Cathedral, Dubuque, Iowa. During the mid-50’s Raymond Roseliep began writing poetry that is less that of a “Catholic priest” and more secular in nature.